Improvements

"The Indian contributes to the revenue just as well as the white

man. He buys taxed goods, he wears taxed clothes, he drinks taxed tea, or

perhaps excised whiskey, just as well as the white man; and according to the

liberal principle (the Liberal party in 1885 opposed Macdonald's plan to expand

the suffrage to some Indians), we are to have taxation without representation

in the case of the poor Indian. . . I can remember how the benevolent

abolitionists brought the uneducated slaves from the Southern States by the

underground railway into Western Canada, where they got homes. And those men,

although unaccustomed to freedom, although just emerging from serfdom, when

they came to Canada and had lived here for three years . . . became voters. . .

And here are Indians, aboriginal Indians, formerly the lords of the soil,

formerly owning the whole of the country. Here they are in their own land,

preventing from either sitting in this House, or voting for men to come here

and represent their interests. There are a hundred and twenty thousand of these

people, who are virtually and actually disenfranchised, who complain, and

justly complain, that they have no representation."

Sir John A. Macdonald, Commons Debates, 30 April

and 4 May 1885, pp. 1488, 1575.

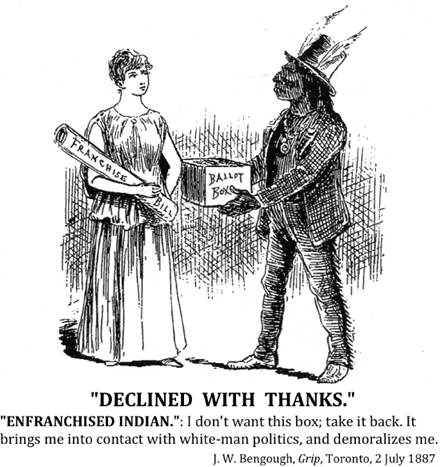

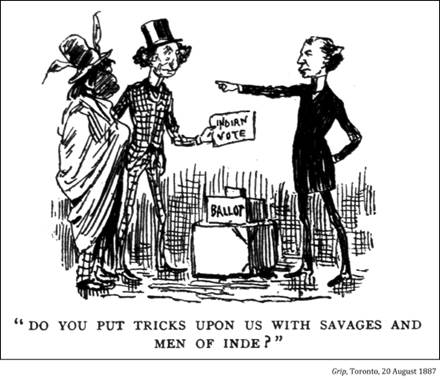

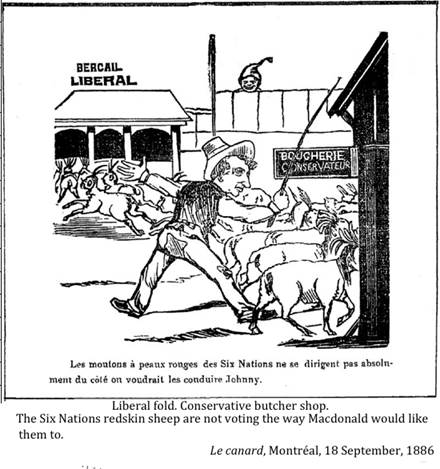

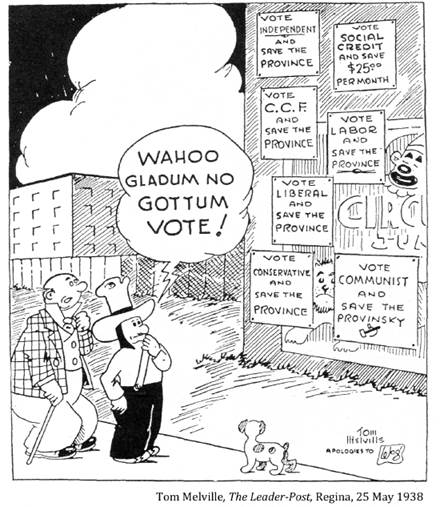

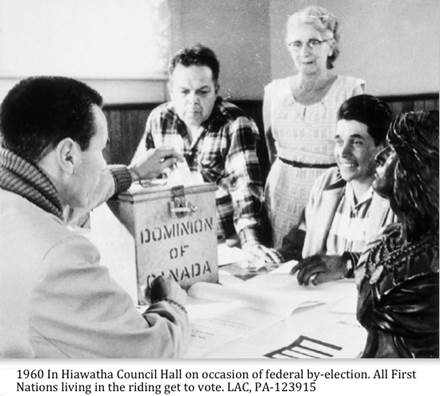

[In

1885 Sir John A. Macdonald's Franchise Act gave all adult Indians living in

eastern Canada the right to vote without, as in the past, having to give up in

exchange any of their special rights as Aboriginals. The Act lasted until 1898

when the franchise was taken away by the Laurier government. Few First Nations

people used the ballot.]

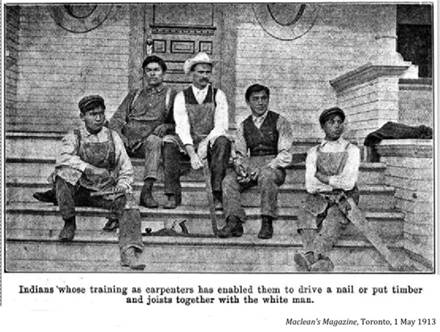

The Acts commonly known as the Gradual Civilization Act of 1857 and

the Gradual Enfranchisement Act of 1869 were almost uniformly aimed at

removing any special distinction or rights afforded First Nations peoples and

at assimilating them into the larger settler population. This was initially

meant to be accomplished by the Gradual Civilization Act through

voluntary enfranchisement (i.e., a First Nations person would relinquish their

status in exchange for land and the right to vote), but only one person

voluntarily enfranchised.

The Canadian Encyclopedia

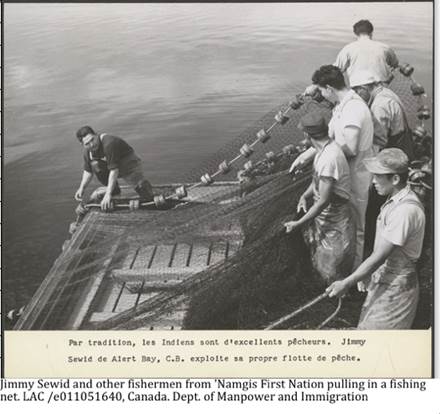

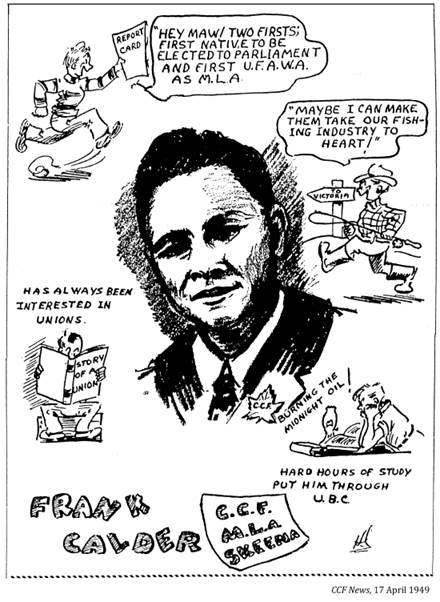

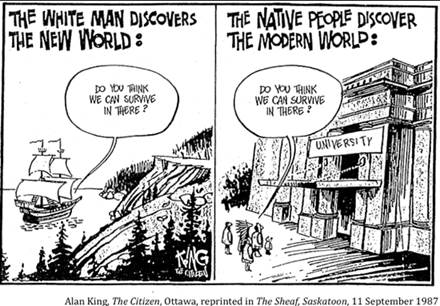

[Frank

Calder was born in the Nass River Valley in northern British Columbia in1915.

At the age of 9 he attended a Methodist mission school at Coqualeetza

for four years, a government funded residential school for four years and the Chilliwack

high school for four years. He returned to the Nass Valley every summer to

fish. Frank Calder was the first aboriginal to graduate from high school, to

graduate from UBC, to be elected to any legislature or parliament and to be

appointed a cabinet minister. He successful fought for title to Nisga's lands.]

Hereditary

Chief Alfred Scow of Gilford Island became the first Aboriginal person in BC to

graduate from law school in 1961.

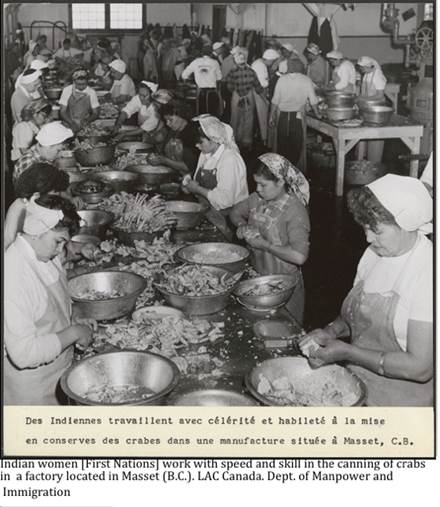

"Teachers

from all over the world, from England, Denmark, Germany, the Philipines, from the United States and Africa. They stay

for one year. . . The teacher will walk up to the school, open the door and,

very often find that the basement has flooded. There is no oil. There is

no electric light. There is no sign of school books or supplies. . . As the

days passed, the teacher started to realize that there were

more important things in the village than education and the school . . .

The whole village was balanced so precariously between survival and disaster

that learning was a form of leisure, having very little connection with the

future. . . If the teacher survived the first year, he would develop an empathy

with the people of the village. If he survived the second year, he would see

the separate identities of each individual, the class structures, the feuds,

the family solidarities and jealousies. He would feel the strength of the

community, the steel blade of a culture normally hidden by the mists of

prejudice and prejudgment. If he survived the third year, he would begin to

hate his own selfish society."

John Gibson, employed by the Department of

Social Welfare on the BC coast, A Small and Charming World, 1972

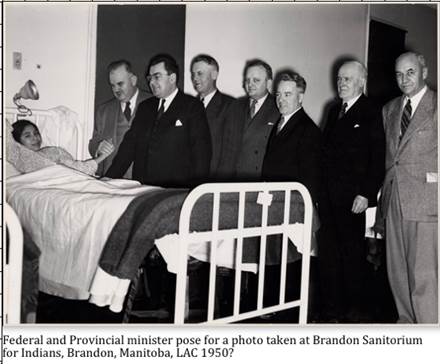

Jordan's

Principle

Jordanís Principle is a child-first principle [passed by the Government

of Canada in December 2007] that ensures First Nations children can access the

same public services as other children in Canada. Jordanís Principle is named

for Jordan River Anderson, a young Cree boy who died at the age of five after

waiting for home-based care that was approved when he was two but never arrived

because of a financial dispute between the federal and provincial governments.

Jordanís Principle was put in place to ensure a tragedy like this never happens

again.

Jordanís Principle is an initiative to ensure that First Nations

children who require support to meet a health, education or social need ó as

recommended by a professional ó can access those services in the same ways as

other children in Canada.

Jennifer Brant, Michelle Filice

Stained Glass Window in Parliament Commemorating the Legacy of Indian Residential Schools, Government of Canada, 2008, https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-INTER-HQ-AI/STAGING/texte-text/sgw_sgwdc_web_1354719933066_eng.pdf